Forget the pandemic – 2020 was the year of the Victorian cast iron range for me.

I tend to be quite faddish with home restoration projects.

On a mission, I decided to pull out both ranges that I installed in 2004/05 in early 2020.

Little did I know I would spend the next six months looking at raw fireplace openings due to the lockdown!

I sourced and installed the first replacement ranges in my kitchen and scullery with little understanding of these fittings. You can see these in my virtual House Tour.

Regrettably, my only criteria was ensuring they fitted the original range openings.

It became clear that my house’s original ranges were very different after studying the openings and seeking expert advice from range specialist Osborne Restorations.

Here’s what I’ve learnt about these historic cooking beasts and how to cook on them!

A range of ranges

Victorian homes in Britain had two possible types of cast iron ranges.

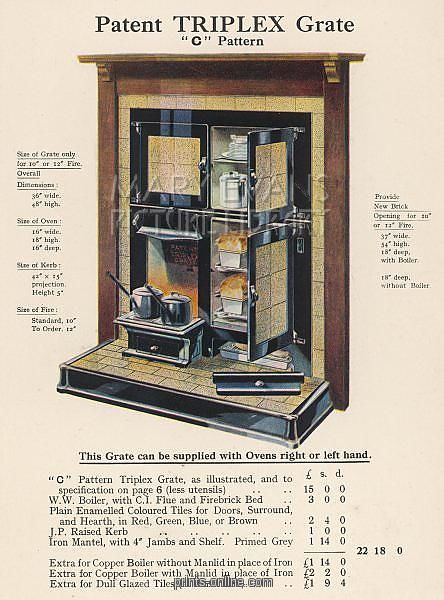

The average range had a grate flanked by an oven and a water boiler or a sham (for standing kettles). Larger houses had two or more ovens.

Nevertheless, your status dictated the type of range you had, like most other aspects of Victorian life.

Closed ranges

Middle and upper classes favoured this type of range as it was the most expensive and efficient.

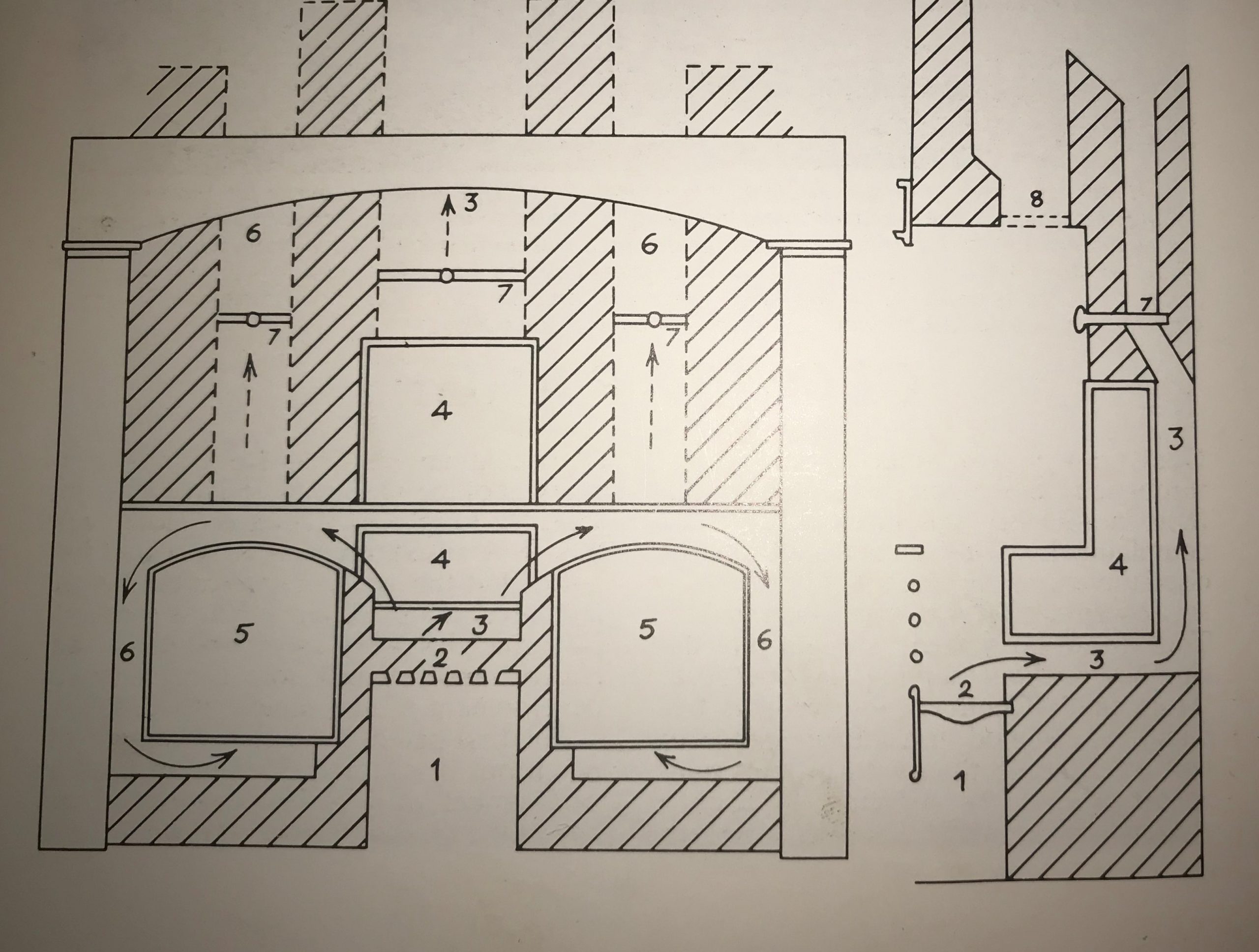

The grate is concealed, meaning less heat escapes into the room and more circulates around the oven before going up the chimney.

However, the grate had a door and removeable top to convert to an open range for roasting and warming the room.

These type of ranges came with matching accessories such as ‘Tidy Betty’ ashpan cover and ornate kettle stands.

The big names at the time such as Flavels, Coalbrookdale and Carron made these ranges.

Open ranges

Standard open ranges

The standard open range was cheaper and was often located in kitchen-cum-living rooms in more modest houses.

This range’s open grate was a good heat source for the average Victorian family who rarely ventured into their parlour!

Its oven was smaller and grate was wider than on a closed range to make up for its heat inefficiency.

The more expensive versions had iron ‘covings’, whereas the cheaper versions required a brick back.

Like the closed range, this type of open range had separate flues for the oven and boiler.

These were linked to vents on the sides of the grate which diverted heat around a channel around the oven.

The heat then escaped underneath the oven and up the separate flue located behind the oven. The cook could control the heat by using eye-level dampers to close off the flue when the oven was no longer required.

Chimney sweepers used ‘soot’ doors located on the coving or brick back to clean these flues to avoid soot build-up.

Open ranges with this type of set-up were often made by a local blacksmith using standard patterns available nationwide – the ‘Excelsior’ was the most common version.

Interestingly, there were also regional variations, such as the ‘Yorkshire’ range with high oven which was often found in the north of England.

Cottage open ranges

These were the cheapest type of range and were often located in kitchens in poorer homes, sculleries and servant’s communal rooms.

Unlike the previous ranges mentioned, these tended to be more decorative with floral or crest cast details on the doors and a moveable trivet over the grate for kettles.

They often came with two ovens as they were very small and the flue set-up was basic, making them fairly inefficient.

The cheapest versions were known as ‘self-acting’ with one central flue for the grate. The oven gained its heat purely from the grate side so the oven was fitted with a revolving plate which could be turned for even cooking.

The other type was known as an ‘ash pit’ range. This had a separate flue under the oven that gained extra heat from falling ashes in the ash pit.

There was a Midland variety with a distinctive wide circular ash pit area.

Cooking on a cast iron range

I’m no expert on this, but I’ve learned a few things cooking on my standard open range in recent months.

Roasting meat isn’t what we know today – it tended to be done over or against the burning grate.

Many Victorians used a ‘bottle-jack’ with a clockwork mechanism to turn the hanging meat.

I have one of these and we cooked a hanging duck on this last Christmas. It took around two hours to roast and gave the skin that gorgeous roasted taste that you don’t get from oven cooking.

The oven tended to be used for baking. It takes up to two hours and lots of coal to get an open range oven up to 180 degrees – slow-cooking casseroles and stews are more suited for these ovens.

Surprisingly, we found smokeless coal doesn’t get that hot and house coal is better. Unfortunately, this type of coal will soon be banned in the UK. Nevertheless, I’ve been advised using smokeless coal with hardwood such as beech can help boost the temperature.

Frying and boiling was carried out on the hob plate over the oven. My range has a removable plate where a pot or pan can stand over. However, we found placing the pan on the grille fitting directly above the grate ensured quicker boiling and frying.

The demise of the cast iron range

Technology and reduced availability of servants were the two main reasons for the demise of the cast-iron range.

Gas ovens became widely available and affordable in the early 20th century. Their advantage was instant heat and no mess to clean up.

For the working classes, small gas ovens could easily fit into their tiny sculleries, allowing them to use their back rooms just as a living space.

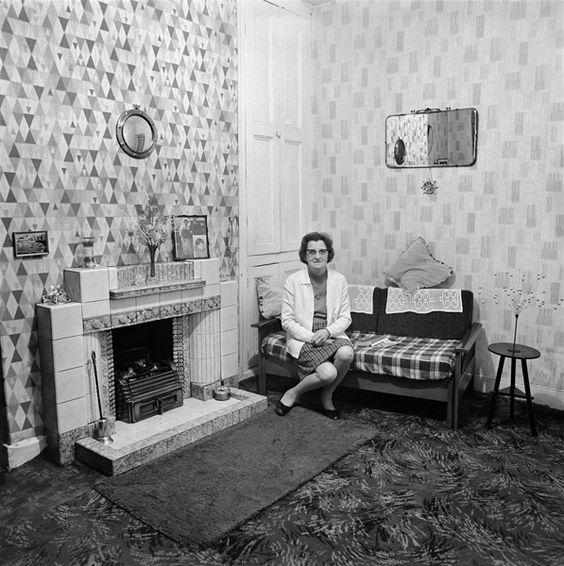

Some replaced their cast iron range with an enamelled and tiled combination range in the 1930s, which was more compact and took on the appearance of an open fire.

In contrast, the middle and upper classes struggled to find servants after the First World War and moving to gas meant they needed less domestic support.

Wealthy households upgraded to enamelled and coke-fired Agas in the 1930s. These were cleaner to use and did not require regular black leading.

Cast iron ranges were still available to buy during the 1930s and Mrs Smith’s cottage museum has a standard open range fitted during this period.

However, the remaining factories ceased cast iron range production at the start of the Second World War to focus on the war effort and did not resume afterwards.

By 1942, around half of UK homes used coal for cooking during the winter months, whereas almost three quarters of homes also used gas.

The majority of ranges were removed from British homes after the war in favour of modern tiled fireplaces.

Yet, I recently learnt the original range in my house was used until 1974 by the lady who lived in my houses from the 1920s.

Further information

To see more photographs of ranges, visit my Pinterest account.

I also have a blog post on reinstating a Victorian fireplace.

Hi there Mr Victorian

It’s me again, I am a big fan of your house and for years, I’ve had the same passion as you and would love to recreate something like this one day but at 18 years old, I’ll probably have to wait a while. I even remember you selling the scullery range on eBay back around mid 2020.

My question for today is that, as you mentioned, house coal will be banned soon in the UK. What other coal alternatives could I use to burn in the range if I was to cook in the oven regularly ?

I read about how in the 1930s people used to fire up their enamelled coke boilers with either anthracite or coke. Could this be an alternative?

I am looking forward to your reply

Yours sincerely

Anas

Thank you! I’ve been told harder woods such as beech (not pine) are good for getting a range to a good heat.

You can still buy anthracite coal in the UK, which is the best quality house coal. It is naturally smokeless, so has not been banned, and is different from standard house coal which was largely bituminous and tended to ‘clag’. Most fuel merchants stock it and it is available online, although it is more expensive than old house coal used to be.

Hi still use my ‘The Belle’ range for cooking and have found that the new smokeless is OK if you use more wood, Oak is good as is Holly. Ash tends to give heat but not sustained for long heat. I found that the oven does a good roast beef joint when it already hot, but it does take a little longer. Keep putting little bit of coal in and it maintains the temperature. I love my range and it not only keeps the cottage warm, but it cooks wonderfully. You can still get spares for them. Also you can use oven racks designed for caravan ovens that expand to help the oven temperature at the bottom of the oven as you can then just move things around to get the optimum for each thing you are cooking. As long as you are aware this is not an electric fan oven and you have to be on top of it all the time, you can get some amazing results. I would recommend you get an oven cloth and make it into an apron as it can get quite hot on the legs whilst cooking on a range of this type, best thing we ever bought was my ‘Belle’

I have tried various smokless coals in readiness for the ban and they are all useless. I had tonne of old type coal delivered this week which is still available from coal merchants for 24 months I think. I am getting half a ton dropped off every month till it’s banned. I am lucky to have plenty of room. I am restoring a pre war yorkist for my back kitchen

I understand woods such as beech are good for burning and getting to a high heat.

Good to someone else has done the same journey. I have refurbished a late Victorian double oven closed range and fitted it into my house where there used to be one. Had to take it out of the cellar in Bournemouth where it lived, rather handy as I could then see how the brick flues were built behind.

Mine works very well on housecoal, gets a very good oven temp, especially the smaller right hand oven, easy to get over 200 deg centigrade, and have actually got it over 300 and burnt the paint off of the small in oven temp dial!

Practice is required, but you soon get to appreciate their flexibilty, great for entertaining guests too on a cool winters evening.

I wonder how many people still use theirs?

Hi David,

I think yours gets to a high temperature as it is a closed oven – a lot of heat escapes into the room with an open one.

I don’t think many use them any more for cooking – some people will use it just as a fire though.

Hallo, I’m just sharing your blog. The reason why it took so long to get your oven up to temperature is the quality of coal available to you. All “House coal” these days is imported brown coal which does not burn well (and is hideously smoky). Your Victorian cook would have had higher quality British coal or even, if they were feeling flush, anthracite. Anthracite burns at a very high temperature and is relatively low in smoke. You’d probably have got your oven up to pastry temperature in under an hour using anthracite.

Traditional recipes designed for coal ranges don’t refer to things like “bake for 20 mins at 180 then drop the oven temperature to 150 for a further 40 minutes”, of course. They will refer often to a “rising oven” or a “falling oven”. If you were canny you could make very efficient use of the heat.

Hi I have a Victorian style range. I would love to get it working. Do you know how I would go about this?

I would get your chimney and the range flues swept and use a smoke bomb to make sure it draws properly and there is no damage to the flues.

Very interesting . I renovate houses and sadly no ranges in but we tend to open up the chimney to put a modern cooking range in. I’m curious as every chimney we open there is a small stoned ‘mullioned’ area on the rear wall , I can’t work out what this was ever for , any ideas?

Sorry I don’t – both my ranges openings had a brick back.

Hi love your blog! I have an old Lancashire cooking range I need to remove and restore and I’m interested in more detail as to how you tackled the brickwork/ gather for the 3 flues also did you use firebrick for the back of the fire opening? Did you line the chimney? Looks like mine has partially collapsed over time so it’s difficult to fathom how it was constructed! Help! 😂 thx Rob

Sorry for the delay in replying. We didn’t line the chimney as the flue was in good condition. The three flues don’t need to taper into one – they just finish above the iron backing and the smoke finds its way up the chimney. These flues are just made up of stacked bricks which are sealed against the iron backing. See my pics to visualise this.