Before the luxury of the electric washing machine, our ancestors had to toil away with their washing in a Victorian copper washing boiler.

The ‘copper’ is now very much a thing of the past and most built-in versions were removed during the 20th century when labour saving gas and electric alternatives became available.

I’ve recently reinstated my house’s copper in the room that was formerly the scullery.

I’ve done much research and here’s what I learnt about these mysterious beasts!

The Victorian copper – a history

The ‘copper’ name came from the material of the washing boiler pan found in big houses. However, most Victorians had a boiling pan made of cheaper cast iron.

The Victorians often housed these pans in a brick structure which was located in the scullery or washing outhouse. However, freestanding ‘portable’ iron versions were also available.

Many were positioned next to a small cast iron range and their flues shared the same chimney stack. This range usually would not have been the house’s main range – this was located in the kitchen.

A Victorian housewife or servant used the copper on washday – typically Monday. At the end of the day, they emptied out the water using a ladle and oiled the iron pan to prevent rust. Posher versions had a built-tap which would drain the water into a bucket.

Interestingly, many households also used their copper to boil puddings wrapped in cloth, including Christmas puddings.

The Victorian copper – how it works

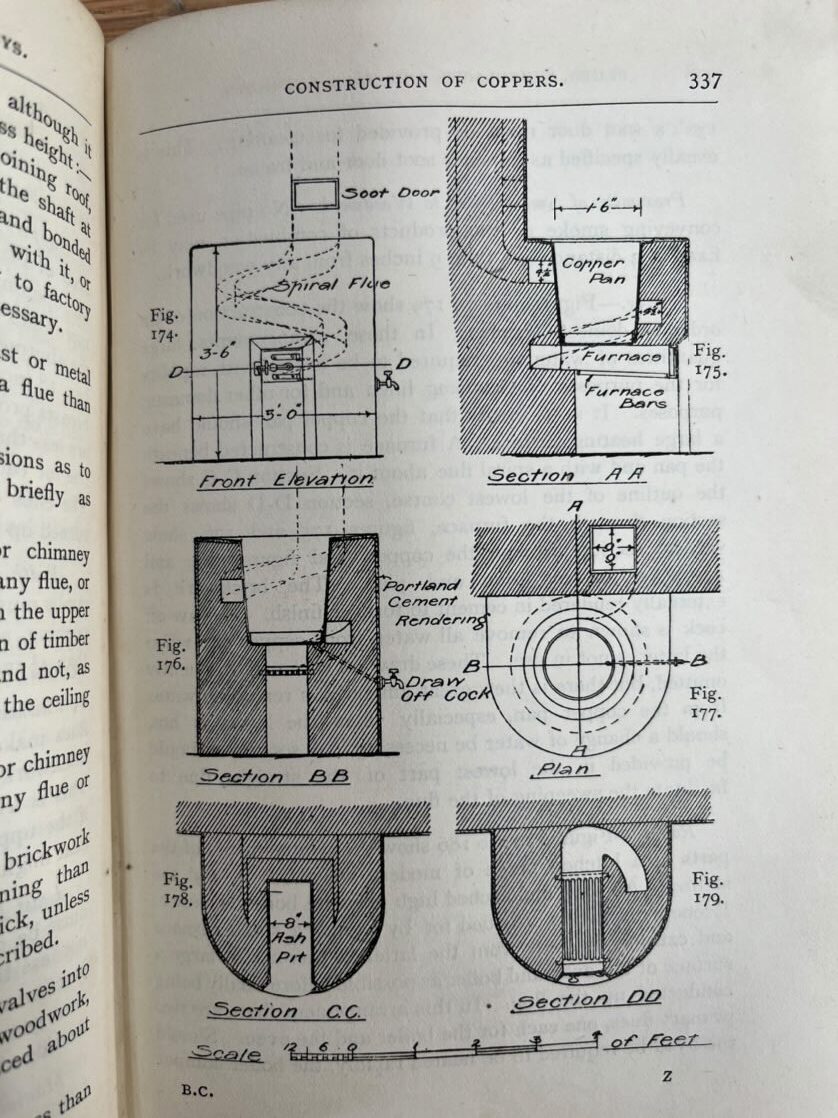

The copper was built with a fire grate below the pan to heat the water, which was accessed through an iron door.

The Victorian housewife or servant used a wooden or copper ‘dolly’ or ‘posser’ to agitate the clothes in the boiling water. The modern washing machine does the same thing with its spinning action.

Better versions had a spiral brick flue built around the washing pan to ensure an even heat. These versions had little iron ‘soot doors’ which allowed easy cleaning around their intricate flues.

However, the average Victorian builder made them more crudely with an open void around the pan’s sides with the heat and smoke escaping up the flue in the structure’s corner. The builder also tended to make the top from concrete.

Some surviving examples appear to have cast concrete tops which were perhaps supplied by a builders’ merchant. However, old photos show some copper tops were crudely smeared with concrete which was applied on site.

The end of an era

The coal-fired copper was dirty, labour intensive and took up a lot of space in the scullery. Therefore, there was a rush to get rid of them when a more convenient option became widely available from the 1930s.

Galvanised gas-fired coppers were their successor. My father remembers his mother used one of these in their 1950s council house.

These gave way to electric twin tubs and then the modern washing machine we know today.

Visit 1900s Social History for more information on Victorian and later coppers.

Interesting post – thank you. I have a concrete-capped recessed feature in the part of my kitchen that was originally the scullery, although the only outlet for smoke seems to be air vent (no chimney) and I think this may have been where the copper was

Probably – they sometimes had a separate iron flue outside which may have been removed. Peter